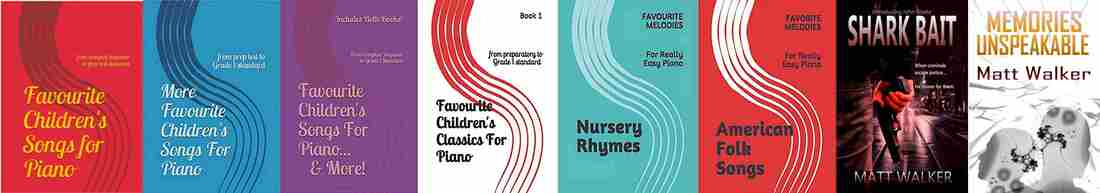

AT NIGHT SHE LIVES

by Matt Walker

First published by Dark Fire Fiction

“Why the hell is he coming with us?” Jay scowled through his white make-up at the younger boy.

“Because my mom said I had to take him.”

“Jesus, Ben.”

“Oh, leave off, Jay. He’s alright.” Ben put a hand on his younger brother’s shoulder. “He just wants to go trick or treating like the other kids.”

“Oh, well that’s just great.” Jay flung out his arms and his pathetic Dracula cape rippled in the October night. “Terrific. So we have to baby-sit an eight-year-old.”

“I’m actually ten.” Ben’s younger brother wore a hockey mask, though his voice came out small and not in the least bit scary.

“Ssh, Owen.” Ben shrugged his shoulders at Jay. His clothes were ripped and covered in fake blood. “He won’t be a nuisance.”

“He better not be. Hear?” Jay prodded Owen in the chest. “Hear?”

Owen looked at his feet and said nothing.

Jay turned back to Ben. “What the hell are you supposed to be, anyway?”

“A zombie, or something, I dunno. Just something dead and mangled.”

“You look like a heap of crap.”

“Well, you look like a woman wearing a face mask.”

Jay gave him the bird.

Ben grinned. “Come on, before it gets too late.”

“Too late? Your mom hasn’t told you to be back by 9 o’clock because of him—” he jabbed a finger at Owen, “—has she? We’re fifteen, Ben!”

“I know.”

“I’m ten.”

“Shut up, Owen.” Jay sighed, and his fangs nearly fell out. “Fine. Let’s get going then, if we’re going to bother.”

Ben nearly threw up his arms and said, “Fine—let’s not bother, you miserable git,” but he would never say something like that to Jay. Later, of course, he wished with all his heart he had.

They went from house to house and tried their best to scare the residents into handing over sweets. (“Or money,” Jay had said, “try and get money, Ben.”) Ben would knock the door with Owen and say, “Trick or treat,” and all without fail would obligingly hand over handfuls of unwanted chocolates and sweets that would soon be out of date or already were.

Jay hid behind the garage, willing a homeowner to say “trick”—possibly with a mischievous glint in their eye—and then Jay would jump out and scream at them and make them crap themselves.

But no one did. It made him angry.

“Why isn’t anyone asking to be tricked?” Jay kicked the gutter.

“Don’t complain; they’re giving us sweets!” Owen grinned, already eating some of the night’s takings.

“Halloween isn’t about the sweets, it’s about scaring people. God, this is lame.”

They got to the end of the road and stood looking at the house on the corner.

“She won’t answer,” Ben said. “She didn’t last year.”

Mrs Lovejoy was an elderly widow, diagnosed as ‘batty’ and ‘off her rocker’ by the neighbourhood kids (and their parents too, truth be told).

“Just ring the doorbell,” Jay said, taking his position out of sight behind the garage.

Ben sighed and did so. To his surprise, Mrs Lovejoy answered almost immediately, as if she’d been waiting to dish out her old sweets to any kid brave enough to ring her doorbell. It’d have been better for everyone if she hadn’t. Especially herself.

“Trick or treat!”

“Ooh, don’t you two look a picture!” the old woman cawed, taking some snack-sized chocolates from the dish on a nearby shelf and dumping them in the sack Owen carried. “Don’t eat them all at once, now.”

“We won’t, thank you very...”

“Roooaaar!” Jay decided to jump out anyway. He’d been dying to all night, and he laughed as he did it. Ben and Owen jumped, and they knew he was there. Mrs Lovejoy gasped. Her eyes bulged.

“Jay, you idiot, that wasn’t funny...”

Jay laughed, and then his smile faltered. Mrs Lovejoy clutched her hand to her chest and choked out short, shallow breaths.

“Mrs Lovejoy... stop screwing around...” But Jay knew as well as anyone that the old lady wasn’t joking. It was etched on his terrified face. “Mrs Lovejoy?”

She fell to the floor and was still.

“Oh crap,” Jay said. “Oh crap.”

* * * * *

“We’ll have to leave her.”

“We can’t leave her!” Ben put both hands to his head. He was suddenly very, very hot.

“She’s dead, isn’t she!” Owen cried until snot came from his nose.

Jay looked over his shoulder. The street was almost completely hidden by the row of trees lining the front garden. “No one can see us. No one needs to know we were here.”

“You killed her!” Ben said.

“She had a heart attack! She was old! It was about time she died.” Jay’s eyes were as wild and feral as a rabid dog’s. “They’ll arrest you, too. You were here with me. They’ll take you away from your mom.”

Owen cried harder.

“Jay...”

“I’m not getting done for this, Ben—they’ll put me inside this time. And everyone will think you’re a murderer too. We have to leave her and tell no one.”

Ben felt his own eyes burning. “I don’t know...”

“Yes. Yes. Promise me. We tell no one.”

And his eyes were so wide and scared and mad that Ben could only nod. “O... okay...” he said.

* * * * *

“Oh no, listen to this, kids.” Their father ruffled the local paper as he said, “Mrs Lovejoy from down the street died of a heart attack last night.”

Ben caught Owen’s eye, feeling his stomach knot. She’d come to him last night, you see. Crawled across the carpet and grabbed his ankle. “Jay will try to blame you for it all...” she’d said. “You can’t trust him...”

The cereal suddenly tasted like cold gruel and sank uncomfortably in his stomach. “A heart attack?”

“Yes. It says she phoned for an ambulance complaining of severe chest pains just before 9 o’clock last night, but she was already dead when they got there.”

The words punched Ben clean in the stomach. “She phoned for an ambulance?” His voice came out muffled and sounded like it belonged to someone else.

“Yes. That’s what it says. Are you alright?”

Oh Jesus, she was still alive when we left her... He closed his eyes, hearing Owen stifle a sob and dash from the table. Oh Jesus Christ of Nazareth... we might have saved her...

“Because my mom said I had to take him.”

“Jesus, Ben.”

“Oh, leave off, Jay. He’s alright.” Ben put a hand on his younger brother’s shoulder. “He just wants to go trick or treating like the other kids.”

“Oh, well that’s just great.” Jay flung out his arms and his pathetic Dracula cape rippled in the October night. “Terrific. So we have to baby-sit an eight-year-old.”

“I’m actually ten.” Ben’s younger brother wore a hockey mask, though his voice came out small and not in the least bit scary.

“Ssh, Owen.” Ben shrugged his shoulders at Jay. His clothes were ripped and covered in fake blood. “He won’t be a nuisance.”

“He better not be. Hear?” Jay prodded Owen in the chest. “Hear?”

Owen looked at his feet and said nothing.

Jay turned back to Ben. “What the hell are you supposed to be, anyway?”

“A zombie, or something, I dunno. Just something dead and mangled.”

“You look like a heap of crap.”

“Well, you look like a woman wearing a face mask.”

Jay gave him the bird.

Ben grinned. “Come on, before it gets too late.”

“Too late? Your mom hasn’t told you to be back by 9 o’clock because of him—” he jabbed a finger at Owen, “—has she? We’re fifteen, Ben!”

“I know.”

“I’m ten.”

“Shut up, Owen.” Jay sighed, and his fangs nearly fell out. “Fine. Let’s get going then, if we’re going to bother.”

Ben nearly threw up his arms and said, “Fine—let’s not bother, you miserable git,” but he would never say something like that to Jay. Later, of course, he wished with all his heart he had.

They went from house to house and tried their best to scare the residents into handing over sweets. (“Or money,” Jay had said, “try and get money, Ben.”) Ben would knock the door with Owen and say, “Trick or treat,” and all without fail would obligingly hand over handfuls of unwanted chocolates and sweets that would soon be out of date or already were.

Jay hid behind the garage, willing a homeowner to say “trick”—possibly with a mischievous glint in their eye—and then Jay would jump out and scream at them and make them crap themselves.

But no one did. It made him angry.

“Why isn’t anyone asking to be tricked?” Jay kicked the gutter.

“Don’t complain; they’re giving us sweets!” Owen grinned, already eating some of the night’s takings.

“Halloween isn’t about the sweets, it’s about scaring people. God, this is lame.”

They got to the end of the road and stood looking at the house on the corner.

“She won’t answer,” Ben said. “She didn’t last year.”

Mrs Lovejoy was an elderly widow, diagnosed as ‘batty’ and ‘off her rocker’ by the neighbourhood kids (and their parents too, truth be told).

“Just ring the doorbell,” Jay said, taking his position out of sight behind the garage.

Ben sighed and did so. To his surprise, Mrs Lovejoy answered almost immediately, as if she’d been waiting to dish out her old sweets to any kid brave enough to ring her doorbell. It’d have been better for everyone if she hadn’t. Especially herself.

“Trick or treat!”

“Ooh, don’t you two look a picture!” the old woman cawed, taking some snack-sized chocolates from the dish on a nearby shelf and dumping them in the sack Owen carried. “Don’t eat them all at once, now.”

“We won’t, thank you very...”

“Roooaaar!” Jay decided to jump out anyway. He’d been dying to all night, and he laughed as he did it. Ben and Owen jumped, and they knew he was there. Mrs Lovejoy gasped. Her eyes bulged.

“Jay, you idiot, that wasn’t funny...”

Jay laughed, and then his smile faltered. Mrs Lovejoy clutched her hand to her chest and choked out short, shallow breaths.

“Mrs Lovejoy... stop screwing around...” But Jay knew as well as anyone that the old lady wasn’t joking. It was etched on his terrified face. “Mrs Lovejoy?”

She fell to the floor and was still.

“Oh crap,” Jay said. “Oh crap.”

* * * * *

“We’ll have to leave her.”

“We can’t leave her!” Ben put both hands to his head. He was suddenly very, very hot.

“She’s dead, isn’t she!” Owen cried until snot came from his nose.

Jay looked over his shoulder. The street was almost completely hidden by the row of trees lining the front garden. “No one can see us. No one needs to know we were here.”

“You killed her!” Ben said.

“She had a heart attack! She was old! It was about time she died.” Jay’s eyes were as wild and feral as a rabid dog’s. “They’ll arrest you, too. You were here with me. They’ll take you away from your mom.”

Owen cried harder.

“Jay...”

“I’m not getting done for this, Ben—they’ll put me inside this time. And everyone will think you’re a murderer too. We have to leave her and tell no one.”

Ben felt his own eyes burning. “I don’t know...”

“Yes. Yes. Promise me. We tell no one.”

And his eyes were so wide and scared and mad that Ben could only nod. “O... okay...” he said.

* * * * *

“Oh no, listen to this, kids.” Their father ruffled the local paper as he said, “Mrs Lovejoy from down the street died of a heart attack last night.”

Ben caught Owen’s eye, feeling his stomach knot. She’d come to him last night, you see. Crawled across the carpet and grabbed his ankle. “Jay will try to blame you for it all...” she’d said. “You can’t trust him...”

The cereal suddenly tasted like cold gruel and sank uncomfortably in his stomach. “A heart attack?”

“Yes. It says she phoned for an ambulance complaining of severe chest pains just before 9 o’clock last night, but she was already dead when they got there.”

The words punched Ben clean in the stomach. “She phoned for an ambulance?” His voice came out muffled and sounded like it belonged to someone else.

“Yes. That’s what it says. Are you alright?”

Oh Jesus, she was still alive when we left her... He closed his eyes, hearing Owen stifle a sob and dash from the table. Oh Jesus Christ of Nazareth... we might have saved her...

* * * * *

Jay awakens during the night, boiling in his pyjamas—swimming in them—and he bites down on his fist to muffle his scream. She comes to him during the night, three or four times, her old wrinkled face contorted and her hands clutched to her chest. He sees her fall, but when he’s alone in bed like this she doesn’t lie still. At night she lives, and she crawls over the carpet towards him, gasping and wheezing. She grabs at his ankles and Jay can’t move—can’t even kick her off, which is what he tries.

“You killed me and left me...” Mrs Lovejoy rasps, and then Jay realises that she is dead after all. “You killed me, and they’re going to tell on you.”

“No, Mrs Lovejoy—I...”

“You’ll go to prison this time, Jay.”

And Jay sits up in his bed, heart thud-thud-thudding (perhaps he’ll have a heart attack himself, a ha ha ha), and he screws his hands into fists and beats them against his temples.

They won’t tell... he says to himself. Pleads to himself. But can he really trust Ben? Certainly not his snivelling runt of a brother.

“They won’t tell, will they?” He says this out loud, asking the darkness. It is silent in his room.

He lies back and closes his eyes. He breathes through his mouth. It takes him a long time to fall back asleep. Mrs Lovejoy will come to him again, later. She will take him to the depths of despair, show him Owen’s laughing face and Ben’s sneer, their relief at the police station where they grass him in. He sees the cops come and arrest him, the judge, the bars. His mom is crying.

And then Mrs Lovejoy will lead him out the other side. And he will know what to do.

* * * * *

Owen didn’t go to school that morning. He told his mom he’d been sick, which in fact was true, and she’d told him in no uncertain terms to go back up to bed. He wasn’t one to bunk off school. And anyway, he looked awful, she said. Owen supposed he did.

Ben came upstairs before he left—he had his mock exams coming up soon and had to go in, he said, or maybe leaving Mrs Lovejoy to die hadn’t affected him as much.

“It’ll be all right,” he said, and squeezed Owen’s shoulder. He didn’t look like he thought it’d be all right—how could it be?—and Owen thought the squeeze was more like a nip. A reminder. Or a warning. Everything will be all right, little bro, as long as you keep your mouth shut.

Owen watched his brother head back downstairs, heard him leave. He felt sick again.

Mrs Lovejoy had come to him during the night, crawled across the carpet and grabbed him by the ankle, holding him to the doorstep. He’d been alone. Utterly alone. And she’d told him that Ben couldn’t be trusted. “He’s always been jealous of you. You being their favourite.”

Owen knew, of course, that their parents favoured him. Ben knew it too. But what did he expect? Ben mixed with the wrong crowd. He smoked and drank. He got into trouble at school. Not a lot, mind, but often enough.

Owen, on the other hand, was smart and hard working and good-natured. He got good grades. His teachers called him an exemplary pupil. Of course their parents favoured him.

“But he doesn’t like it,” Mrs Lovejoy had said. “Oh no. And he’ll use this as a way to disgrace you. He’ll tell your parents that you begged to leave me. Owen goody-two-shoes simply couldn’t get into trouble with the police. And your parents will believe him and suddenly you won’t be their favourite anymore. They’ll probably die of shame.”

Owen sat down on the bed. He thought he might cry, though no tears came. He was glad. He was done with crying. He wouldn’t cry in front of Ben again, anyway. When would Ben tell their parents? When he got home from school, probably. Owen thought about going downstairs right away and telling his mom exactly what had happened. But he didn’t. He couldn’t.

He went into the kitchen and found the local paper his dad had been reading. The snippet on Mrs Lovejoy was on page 4. He read it three times over, hoping the words might change if he did. She called for an ambulance. We left her and she was still alive. Eventually, he cut the article out of the paper, took it up to his room and folded it away in one of his drawers. If he couldn’t save Mrs Lovejoy herself he’d save her obituary. Just paper and ink. He saved it. Then he lay down and curled up his body and hoped it’d all go away.

Ben got home just after 4 o’clock and disappeared into his room across the landing. Owen would keep an ear out, just in case Ben went tattling to their mother, trying to blame him. He knew it would happen; it was just a matter of time.

At 5 o’clock he heard Ben talking, and his insides knotted. Except mom was still downstairs—he could hear her in the kitchen messing with the oven.

Owen left his room and crossed the landing as quietly as he could. The floor creaked. Goddamn it. Ben’s voice didn’t falter, though. His door stood ajar a smidge, and Owen pushed it open.

Ben looked up at him. He was on his mobile. “Yes, okay, I’ll bring him.” A sigh. “Yes, see you later.” He hung up. Looked at his little brother. Sighed again. “We have to meet up with Jay tonight.”

Owen felt nothing. “Why?”

“Talk through what happened. What we’re going to do. Jay seemed...” Ben cut off with a shake of his head. “Oh, I don’t know.”

“I don’t want to go.”

“We’re meeting at the clubhouse. You’re always asking me to take you to the clubhouse.”

Owen stared at him. “Not like this.” I wanted you to take me there and play pool with me. Or ping pong. But no. I’m only your stupid kid brother, aren’t I? You only take me there after we kill an old lady.

He went though. He wanted to see what it was like inside.

* * * * *

Ben told Mom that they were going to a friend's. Once upon a time that might have been true. She happily believed him though—it wasn’t often Ben included Owen in something of his own free will.

The clubhouse sat like an old barn in the middle of the paddock. The brownies used it on Mondays, the cubs on Fridays, and then there was a youth club every Saturday night. Tonight was Thursday. It was empty.

Jay and his friends had discovered long ago that you could jig up the bolt on the storeroom and get in. You couldn’t get through to the rest of the building—but who cared? The storeroom had the pool table. They would play pool or darts, or maybe even a card game if they were feeling civilised, and drink cans of beer or alcopops. Once, Hannah Gleeson had brought a bottle of vodka and then been sick all over the floor. Hannah wasn’t invited anymore.

Tonight, Jay waited alone for them. He leant on the pool table, and Owen thought that in the past day he’d aged fifty years and his eyes seemed too large for his head. Jay wore a smile, too. A big one.

“Close the door.”

Ben closed it. Licked his lips. “We haven’t told anyone,” he said.

Jay nodded. “Good. Neither have I. She was still alive, you know. When we left her.”

“Yes. It was in the paper.”

Owen put his hands in his coat pockets and hunched his head like a turtle. The storeroom was long and filled with rows of metal cabinets. Books. Games. Art materials. The far end of the room was in darkness. The only lit bulb hung above the pool table and bathed Jay in sick bronze light.

Ben ambled up to his friend and said to him. “I think we should tell them what happened.”

Owen expected Jay to protest, to scowl or something. Instead, he nodded.

“She told me you’d think that.”

“Who...”

“And I can’t let you, Ben. I’m sorry.” And Jay punched him in the stomach, hard.

Ben’s eyes bulged and he bent double, hands going to his midriff, and that’s when Jay pulled free and Owen saw the knife. It was covered in blood and winked in the light.

Owen gasped, wanted to scream, but could not find his voice.

Jay stabbed again, and this time Ben fell to the floor, wet breaths sucked from his throat. Jay followed him down and stabbed a third time, this one in the chest, and the knife only went half way in.

Owen wanted to dive to his brother’s aid, to jump on Jay and wrench the knife from him, and possibly give him a good kicking. Instead, he pissed himself.

“O... Owen...” Ben lay in a pool of his own blood, clawed hand outstretched, reaching for him, for help.

Jay sat on top of him, working the knife free of Ben’s chest. His cheek was dotted with blood. He was smiling. “Going to tell on me now, eh?” He laughed, and there was not an inch of sanity in that laugh. Owen knew it. Jay had gone completely mad.

Finally, Owen got his legs working, and they didn’t take him forward, they took him further back into the storeroom, into the darkness between the metal cabinets. He looked back when he heard Jay singing.

“All things bright and beautiful, all creatures great and small.” Jay stood up. Ben was still twitching—that was good, that was...

“Did I do it well, Mrs Lovejoy?” Jay flicked the knife, and blood made a comet tail on the concrete. “I’m nearly done, and then no one will know what happened to you. No one.” He must have seen which aisle Owen took—or else he guessed lucky—because he began walking over Owen’s footsteps into the gloom. “Owen? Owen!” he called.

Owen slunk down in the shadows as quietly as he could. He followed the aisle until he found the far wall, and then a ghost played over his spine. The cabinets kissed the wall and there was no way to circle back around them.

“Owen!” Jay’s silhouette filled the aisle, coming closer, trailing the knife over the metal shelves and setting it off singing. “Where are you?”

It’s a game to him. Jay had gone totally out of his mind. Owen looked around for a weapon but could barely see a thing in the gloom. His fingers found bottles of paint, a box of fabric, jars of glitter. There was a heavy sack of powder, perhaps modelling clay or plaster of paris. Maybe if he was older and stronger he’d be able to swing it at Jay’s head—it’d probably knock him out—not that it was any use to him now.

No weapon and nowhere to hide. And Jay was getting closer. Could he go over the cabinets? He might be able to climb them, but the ceiling was low—almost brushed the top if he remembered correctly. Could he go under? No—there was no space to go under...

“Owen, I can smell your piss!”

But could he go through? He shoved his arm through the bottles of paint and sure enough it went straight through and out the other side. There was no central stanchion to the cabinets. He heard the bottles of paint roll off the shelf and hit the floor on the other side.

Perhaps Jay realised then what Owen had discovered, because he broke into a run. Or perhaps he could finally make out Owen’s shape in the darkness. Or perhaps he really could smell his piss. Or maybe he was just hungry to stab again.

Owen wriggled his body through the shelves. The cabinet rocked, and for a horrible moment he thought it was going to tip over on him. It steadied though, and spilled him into the adjacent aisle just as Jay reached the far wall.

“Owen, where are you, you naughty boy!”

Owen didn’t think. He braced his feet against the cabinet and pushed with all his might. He felt the legs leave the ground, and the burning in his thighs and calves lessened. The cabinet toppled, spilling its contents from the shelves.

Jay turned as the cabinet bore down on him. He screamed, tried to pull away, but the cabinet was too tall and it caught him. Something big and heavy fell on his head, bringing him down, and then cracked on the floor and spilled out hundreds of beads or building blocks—no: bolts and nails. Owen could see them now; a tool box. The cabinet hit Jay in the neck and something snapped, the sound like a breaking branch. It fell on him, pinned him down, and finally everything was still.

Owen felt his breathing return to normal. He knew that Jay was dead, his neck broken. He didn’t know how he knew, only that it had happened.

“Good,” Mrs Lovejoy whispered to him. It was night time, and at night she lives. “That’s exactly what he deserved, isn’t that right, Owen.”

“Yes, Mrs Lovejoy.” Owen walked back up the aisle to the pool table. He stood over Ben’s bloody body. His brother was still alive, breathing shallow and wet, eyes half-closed. He’d need an ambulance right away.

“But you know what he’ll do, don’t you,” said Mrs Lovejoy. “He’ll blame you for everything. He’ll say all this was your idea. You won’t be favourite then, will you? Not when you’re in prison. He’ll take everything away from you.”

“Yes, Mrs Lovejoy.” Owen knew what he had to do. He took Ben’s phone from his pocket, wiped off the blood. And then threw it into the corner. He heard it crack like a walnut shell. Then he opened the door and walked out into the night, humming All Things Bright And Beautiful as he went.

Jay awakens during the night, boiling in his pyjamas—swimming in them—and he bites down on his fist to muffle his scream. She comes to him during the night, three or four times, her old wrinkled face contorted and her hands clutched to her chest. He sees her fall, but when he’s alone in bed like this she doesn’t lie still. At night she lives, and she crawls over the carpet towards him, gasping and wheezing. She grabs at his ankles and Jay can’t move—can’t even kick her off, which is what he tries.

“You killed me and left me...” Mrs Lovejoy rasps, and then Jay realises that she is dead after all. “You killed me, and they’re going to tell on you.”

“No, Mrs Lovejoy—I...”

“You’ll go to prison this time, Jay.”

And Jay sits up in his bed, heart thud-thud-thudding (perhaps he’ll have a heart attack himself, a ha ha ha), and he screws his hands into fists and beats them against his temples.

They won’t tell... he says to himself. Pleads to himself. But can he really trust Ben? Certainly not his snivelling runt of a brother.

“They won’t tell, will they?” He says this out loud, asking the darkness. It is silent in his room.

He lies back and closes his eyes. He breathes through his mouth. It takes him a long time to fall back asleep. Mrs Lovejoy will come to him again, later. She will take him to the depths of despair, show him Owen’s laughing face and Ben’s sneer, their relief at the police station where they grass him in. He sees the cops come and arrest him, the judge, the bars. His mom is crying.

And then Mrs Lovejoy will lead him out the other side. And he will know what to do.

* * * * *

Owen didn’t go to school that morning. He told his mom he’d been sick, which in fact was true, and she’d told him in no uncertain terms to go back up to bed. He wasn’t one to bunk off school. And anyway, he looked awful, she said. Owen supposed he did.

Ben came upstairs before he left—he had his mock exams coming up soon and had to go in, he said, or maybe leaving Mrs Lovejoy to die hadn’t affected him as much.

“It’ll be all right,” he said, and squeezed Owen’s shoulder. He didn’t look like he thought it’d be all right—how could it be?—and Owen thought the squeeze was more like a nip. A reminder. Or a warning. Everything will be all right, little bro, as long as you keep your mouth shut.

Owen watched his brother head back downstairs, heard him leave. He felt sick again.

Mrs Lovejoy had come to him during the night, crawled across the carpet and grabbed him by the ankle, holding him to the doorstep. He’d been alone. Utterly alone. And she’d told him that Ben couldn’t be trusted. “He’s always been jealous of you. You being their favourite.”

Owen knew, of course, that their parents favoured him. Ben knew it too. But what did he expect? Ben mixed with the wrong crowd. He smoked and drank. He got into trouble at school. Not a lot, mind, but often enough.

Owen, on the other hand, was smart and hard working and good-natured. He got good grades. His teachers called him an exemplary pupil. Of course their parents favoured him.

“But he doesn’t like it,” Mrs Lovejoy had said. “Oh no. And he’ll use this as a way to disgrace you. He’ll tell your parents that you begged to leave me. Owen goody-two-shoes simply couldn’t get into trouble with the police. And your parents will believe him and suddenly you won’t be their favourite anymore. They’ll probably die of shame.”

Owen sat down on the bed. He thought he might cry, though no tears came. He was glad. He was done with crying. He wouldn’t cry in front of Ben again, anyway. When would Ben tell their parents? When he got home from school, probably. Owen thought about going downstairs right away and telling his mom exactly what had happened. But he didn’t. He couldn’t.

He went into the kitchen and found the local paper his dad had been reading. The snippet on Mrs Lovejoy was on page 4. He read it three times over, hoping the words might change if he did. She called for an ambulance. We left her and she was still alive. Eventually, he cut the article out of the paper, took it up to his room and folded it away in one of his drawers. If he couldn’t save Mrs Lovejoy herself he’d save her obituary. Just paper and ink. He saved it. Then he lay down and curled up his body and hoped it’d all go away.

Ben got home just after 4 o’clock and disappeared into his room across the landing. Owen would keep an ear out, just in case Ben went tattling to their mother, trying to blame him. He knew it would happen; it was just a matter of time.

At 5 o’clock he heard Ben talking, and his insides knotted. Except mom was still downstairs—he could hear her in the kitchen messing with the oven.

Owen left his room and crossed the landing as quietly as he could. The floor creaked. Goddamn it. Ben’s voice didn’t falter, though. His door stood ajar a smidge, and Owen pushed it open.

Ben looked up at him. He was on his mobile. “Yes, okay, I’ll bring him.” A sigh. “Yes, see you later.” He hung up. Looked at his little brother. Sighed again. “We have to meet up with Jay tonight.”

Owen felt nothing. “Why?”

“Talk through what happened. What we’re going to do. Jay seemed...” Ben cut off with a shake of his head. “Oh, I don’t know.”

“I don’t want to go.”

“We’re meeting at the clubhouse. You’re always asking me to take you to the clubhouse.”

Owen stared at him. “Not like this.” I wanted you to take me there and play pool with me. Or ping pong. But no. I’m only your stupid kid brother, aren’t I? You only take me there after we kill an old lady.

He went though. He wanted to see what it was like inside.

* * * * *

Ben told Mom that they were going to a friend's. Once upon a time that might have been true. She happily believed him though—it wasn’t often Ben included Owen in something of his own free will.

The clubhouse sat like an old barn in the middle of the paddock. The brownies used it on Mondays, the cubs on Fridays, and then there was a youth club every Saturday night. Tonight was Thursday. It was empty.

Jay and his friends had discovered long ago that you could jig up the bolt on the storeroom and get in. You couldn’t get through to the rest of the building—but who cared? The storeroom had the pool table. They would play pool or darts, or maybe even a card game if they were feeling civilised, and drink cans of beer or alcopops. Once, Hannah Gleeson had brought a bottle of vodka and then been sick all over the floor. Hannah wasn’t invited anymore.

Tonight, Jay waited alone for them. He leant on the pool table, and Owen thought that in the past day he’d aged fifty years and his eyes seemed too large for his head. Jay wore a smile, too. A big one.

“Close the door.”

Ben closed it. Licked his lips. “We haven’t told anyone,” he said.

Jay nodded. “Good. Neither have I. She was still alive, you know. When we left her.”

“Yes. It was in the paper.”

Owen put his hands in his coat pockets and hunched his head like a turtle. The storeroom was long and filled with rows of metal cabinets. Books. Games. Art materials. The far end of the room was in darkness. The only lit bulb hung above the pool table and bathed Jay in sick bronze light.

Ben ambled up to his friend and said to him. “I think we should tell them what happened.”

Owen expected Jay to protest, to scowl or something. Instead, he nodded.

“She told me you’d think that.”

“Who...”

“And I can’t let you, Ben. I’m sorry.” And Jay punched him in the stomach, hard.

Ben’s eyes bulged and he bent double, hands going to his midriff, and that’s when Jay pulled free and Owen saw the knife. It was covered in blood and winked in the light.

Owen gasped, wanted to scream, but could not find his voice.

Jay stabbed again, and this time Ben fell to the floor, wet breaths sucked from his throat. Jay followed him down and stabbed a third time, this one in the chest, and the knife only went half way in.

Owen wanted to dive to his brother’s aid, to jump on Jay and wrench the knife from him, and possibly give him a good kicking. Instead, he pissed himself.

“O... Owen...” Ben lay in a pool of his own blood, clawed hand outstretched, reaching for him, for help.

Jay sat on top of him, working the knife free of Ben’s chest. His cheek was dotted with blood. He was smiling. “Going to tell on me now, eh?” He laughed, and there was not an inch of sanity in that laugh. Owen knew it. Jay had gone completely mad.

Finally, Owen got his legs working, and they didn’t take him forward, they took him further back into the storeroom, into the darkness between the metal cabinets. He looked back when he heard Jay singing.

“All things bright and beautiful, all creatures great and small.” Jay stood up. Ben was still twitching—that was good, that was...

“Did I do it well, Mrs Lovejoy?” Jay flicked the knife, and blood made a comet tail on the concrete. “I’m nearly done, and then no one will know what happened to you. No one.” He must have seen which aisle Owen took—or else he guessed lucky—because he began walking over Owen’s footsteps into the gloom. “Owen? Owen!” he called.

Owen slunk down in the shadows as quietly as he could. He followed the aisle until he found the far wall, and then a ghost played over his spine. The cabinets kissed the wall and there was no way to circle back around them.

“Owen!” Jay’s silhouette filled the aisle, coming closer, trailing the knife over the metal shelves and setting it off singing. “Where are you?”

It’s a game to him. Jay had gone totally out of his mind. Owen looked around for a weapon but could barely see a thing in the gloom. His fingers found bottles of paint, a box of fabric, jars of glitter. There was a heavy sack of powder, perhaps modelling clay or plaster of paris. Maybe if he was older and stronger he’d be able to swing it at Jay’s head—it’d probably knock him out—not that it was any use to him now.

No weapon and nowhere to hide. And Jay was getting closer. Could he go over the cabinets? He might be able to climb them, but the ceiling was low—almost brushed the top if he remembered correctly. Could he go under? No—there was no space to go under...

“Owen, I can smell your piss!”

But could he go through? He shoved his arm through the bottles of paint and sure enough it went straight through and out the other side. There was no central stanchion to the cabinets. He heard the bottles of paint roll off the shelf and hit the floor on the other side.

Perhaps Jay realised then what Owen had discovered, because he broke into a run. Or perhaps he could finally make out Owen’s shape in the darkness. Or perhaps he really could smell his piss. Or maybe he was just hungry to stab again.

Owen wriggled his body through the shelves. The cabinet rocked, and for a horrible moment he thought it was going to tip over on him. It steadied though, and spilled him into the adjacent aisle just as Jay reached the far wall.

“Owen, where are you, you naughty boy!”

Owen didn’t think. He braced his feet against the cabinet and pushed with all his might. He felt the legs leave the ground, and the burning in his thighs and calves lessened. The cabinet toppled, spilling its contents from the shelves.

Jay turned as the cabinet bore down on him. He screamed, tried to pull away, but the cabinet was too tall and it caught him. Something big and heavy fell on his head, bringing him down, and then cracked on the floor and spilled out hundreds of beads or building blocks—no: bolts and nails. Owen could see them now; a tool box. The cabinet hit Jay in the neck and something snapped, the sound like a breaking branch. It fell on him, pinned him down, and finally everything was still.

Owen felt his breathing return to normal. He knew that Jay was dead, his neck broken. He didn’t know how he knew, only that it had happened.

“Good,” Mrs Lovejoy whispered to him. It was night time, and at night she lives. “That’s exactly what he deserved, isn’t that right, Owen.”

“Yes, Mrs Lovejoy.” Owen walked back up the aisle to the pool table. He stood over Ben’s bloody body. His brother was still alive, breathing shallow and wet, eyes half-closed. He’d need an ambulance right away.

“But you know what he’ll do, don’t you,” said Mrs Lovejoy. “He’ll blame you for everything. He’ll say all this was your idea. You won’t be favourite then, will you? Not when you’re in prison. He’ll take everything away from you.”

“Yes, Mrs Lovejoy.” Owen knew what he had to do. He took Ben’s phone from his pocket, wiped off the blood. And then threw it into the corner. He heard it crack like a walnut shell. Then he opened the door and walked out into the night, humming All Things Bright And Beautiful as he went.